About the Author

Miranda Wade received her B.S. in Biological Science from Colorado State University and her dual PhD in Integrative Biology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior from Michigan State University. During her time in the Meek Lab at MSU, her work consisted of using ‘omics to address various conservation questions in both a rare desert plant facing land-use change and the molecular consequences of microplastics exposure in a model fish species. She is currently the Social Media Editor for the American Genetic Association and a PostDoc in the Sin Lab at the University of Hong Kong. For her postdoctoral work, she is exploring the genomic basis of coloration in birds. She is the proud owner/caretaker of three cats.

received her B.S. in Biological Science from Colorado State University and her dual PhD in Integrative Biology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior from Michigan State University. During her time in the Meek Lab at MSU, her work consisted of using ‘omics to address various conservation questions in both a rare desert plant facing land-use change and the molecular consequences of microplastics exposure in a model fish species. She is currently the Social Media Editor for the American Genetic Association and a PostDoc in the Sin Lab at the University of Hong Kong. For her postdoctoral work, she is exploring the genomic basis of coloration in birds. She is the proud owner/caretaker of three cats.

Did you know that the AGA has a long history of publishing about cats? Not just the beloved felines that have commandeered many homes and communities (not to mention ecologically devastating many areas…), but also their wild brethren. In fact, Darwin even mentioned cats in his Origin of Species, where he discussed the relationships between both blue eyes and deafness as well as calico coloration and sex. In the next few blog posts I am going to describe some of the work published about our feline friends in the Journal of Heredity. A reminder to all our members, you get free access to the articles mentioned from your membership homepage on the website!

While cats were first mentioned in some articles regarding the differences between domesticated and wild coloration, the first article specifically concerning cats originates over 100 years ago, in 1917.

ANCESTRY OF THE CAT: Tabby an Animal of Mixed Blood—Egyptian Wild Cat Probably First Domesticated and Has Crossed with Other Cats in Many Lands to Which It Was Taken by the Phoenicians

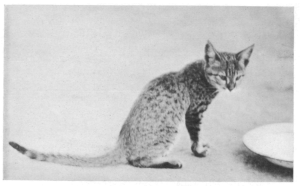

This article posits that domestic cats did not come from the European wildcat (called Felis catus by the author, but we now call the European wildcat Felis silvestris and the domestic cat Felis catus), but instead from the African wildcat Felis libyca. The author posits (using some sketchy and quite patronizing language that I am glad to say mostly dies out in the articles as the decades progress…) that the domestic cat originated in Egypt, was adopted by the Phoenicians, made it to Rome, and then it was off for a European adventure. The so-called Egyptian cat then crossed with the European wildcat (which we know is still problem today, but I am getting ahead of myself here) and some others to get the lovely domestic cats we have today.

What did the author think were ‘other’ wild cats contributing to the domestic cat? Well, they though that the Pallas Cat (called Felis manul but know widely recognized as Otocolobus manul, and actually quite diverged from the Felis lineage) was the ancestor of Angora and Persian cats (aka the fluffy ones). The author does not specifically mention any other species contributing to the domestic cat after this (actually, I don’t think the author of the article is actually known anymore) but overall an interesting first article about cats for the Journal!

Our next article about cats is from none other than Sewall Wright (a giant in population genetics, but thankfully probably not a eugenicist…) in 1918.

COLOR INHERITANCE IN MAMMALS: X., The Cat—Curious Association of Deafness with Blue-eyed White Color and of Femaleness with Tortoise-shelled Color, Long Known—Variations of Tiger Pattern Present Interesting Features.

I am truly impressed by the titles of yesteryear.

In this article,

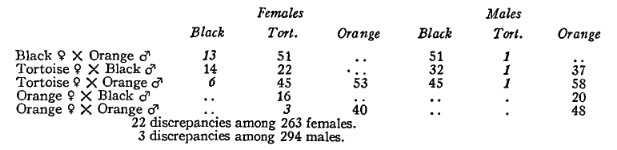

Wright mentions some of the first work investigating the origins of all-white coats in cats (he specifically mentions what we now know as dominant white) as well as the likelihood of some heritable genetic component to heterochromia in felines. By the time her wrote the article, it seemed at least one form of dilution in cats had been worked out, but the genetic control of how Siamese cats gained their points (we now know that the coloration comes from a temperature-sensitive enzyme in a phenomenon known as acromelanism, but again, I am getting ahead of myself).Wright provides a beautiful example of good ole’ pedigree-based genetics wherein scientists (and, in some cases hobbyists/breeders) try to work out the mode of inheritance for a particular trait of interest. The general thought was that orange/black genes must be carried on the X sex chromosome, and interact in such a way that if females are heterozygous for the colors they express both. Wright then beautiful puts forth that the occurrence of some male tortoiseshell cats may indicate those males have two X chromosomes instead of the customary one.

Wright mentions some of the first work investigating the origins of all-white coats in cats (he specifically mentions what we now know as dominant white) as well as the likelihood of some heritable genetic component to heterochromia in felines. By the time her wrote the article, it seemed at least one form of dilution in cats had been worked out, but the genetic control of how Siamese cats gained their points (we now know that the coloration comes from a temperature-sensitive enzyme in a phenomenon known as acromelanism, but again, I am getting ahead of myself).Wright provides a beautiful example of good ole’ pedigree-based genetics wherein scientists (and, in some cases hobbyists/breeders) try to work out the mode of inheritance for a particular trait of interest. The general thought was that orange/black genes must be carried on the X sex chromosome, and interact in such a way that if females are heterozygous for the colors they express both. Wright then beautiful puts forth that the occurrence of some male tortoiseshell cats may indicate those males have two X chromosomes instead of the customary one.

Wright’s final section in his article covers tabby coloration, which is most often considered an ancestral color pattern from the Felidae ancestors of domestic cats. He even circles around to tabby tortoiseshell cats and discusses how tabby appears to act dominant to black and affect the color-producing enzymes (he refers to them as enzyme I and enzyme II, which may be due to tyrosinase not being definitively linked to melanin production until the 1950s). He also supposes that there were several alleles at work in producing the various tabby patterns, which her refers to as finely lined (maybe ticked tabby), blotched (classic tabby), and striped (mackerel tabby). Nowadays, another form of tabby, spotted, is also recognized, and we know that there are actually two loci responsible for the patterning (see here for an open-access overview of those findings).

These two papers round out the earliest articles found explicitly mentioning cats. Stay tuned for the next decade (or maybe two) of Journal of Heredity publishing works featuring cats!