About the Author

Miranda Wade received her B.S. in Biological Science from Colorado State University and her dual PhD in Integrative Biology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior from Michigan State University. During her time in the Meek Lab at MSU, her work consisted of using ‘omics to address various conservation questions about land-use change and microplastics exposure. She is currently the Social Media Editor for the American Genetic Association and a PostDoc in the Sin Lab at the University of Hong Kong. For her postdoctoral work, she is exploring the genomic basis of coloration in birds. She is the proud owner/caretaker of three cats.

received her B.S. in Biological Science from Colorado State University and her dual PhD in Integrative Biology and Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior from Michigan State University. During her time in the Meek Lab at MSU, her work consisted of using ‘omics to address various conservation questions about land-use change and microplastics exposure. She is currently the Social Media Editor for the American Genetic Association and a PostDoc in the Sin Lab at the University of Hong Kong. For her postdoctoral work, she is exploring the genomic basis of coloration in birds. She is the proud owner/caretaker of three cats.

Did you know that the AGA has a long history of publishing about cats? Not just the beloved felines that have commandeered many homes and communities (not to mention ecologically devastating many areas…), but also their wild brethren. In fact, Darwin even mentioned cats in his Origin of Species, where he discussed the relationships between both blue eyes and deafness as well as calico coloration and sex. In the next few blog posts I am going to describe some of the work published about our feline friends in the Journal of Heredity. A reminder to all our members, you get free access to the articles mentioned from your membership homepage on the website!

This post concerns the articles published in the 1920s. The next three articles are all about tortoiseshell cats. At this time, it was common knowledge that male tortoiseshell/calico cats were rare and often sterile, but the mystery of their occurrence had yet to be fully revealed.

THE GENETIC SIGNIFICANCE OF INTRA-UTERINE SEX RATIOS AND DEGENERATING FETUSES IN THE CAT

This article introduces the idea that male tortoiseshell cats may be a form of freemartin, a phrase borrowed from cattle-raisers where a female calf, when she has a male twin, can be sterile due to placental sharing resulting in the circulating of masculinizing hormones from the male calf. To investigate if this was the case in calico toms, the author, EE Jones (likely Eva Elizabeth Jones) undertook over 100 dissections of pregnant cats (sourced from the SPCA of New York City) to determine if there were cases of shared blood supply between kittens and if there was a difference in intrauterine mortality between the sexes of kittens. Jones found no such ‘freemartin’ kittens and thus concluded that male calicos were not likely to be produced via a spillover of hormones during development.

Of particular interest to Jones was if white females had greater incidence of ‘degenerating fetuses’ compared to other colors of females. She found that the overall incidence of nonviable offspring was over 3 times higher in the white cats! Given the rarity of the color it was likely the sire of the respective degenerating litters was not a white cat, and therefore Jones thought it likely there must be some other issues associated with a dominant white pattern and pregnancy viability. It is now widely accepted that white cats, while prone to deafness and certain cancers due to the lack of melanin, do not have a higher incidence of pregnancy issues.

THE TORTOISESHELL CAT

This paper aimed to answer two of the most pressing questions of the time:

- Why are tortoiseshell males rare?

- What are tortoiseshell males sterile?

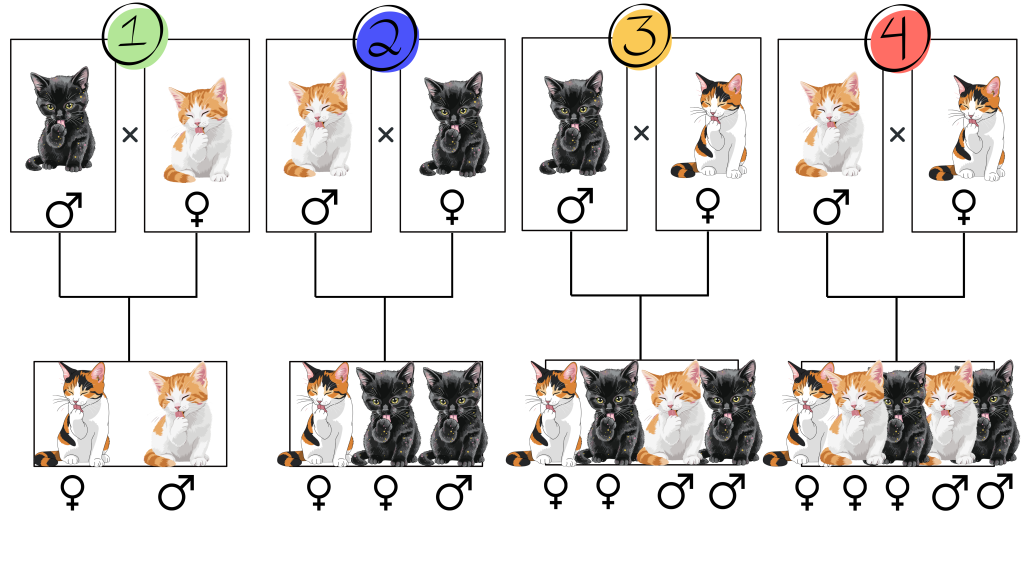

Consider these four scenarios (illustrated below):

- black tom x orange queen = calico females and orange males

- orange tom x black queen = calico & black females and black males

- black tom x calico queen = calico & black females and orange & black males

- orange tom x calico queen = calico & orange & black females and orange & black males

The author of the article (I am not going to mention their name because they were probably a eugenicist, which is just nasty) posits that this means the gene(s) controlling the black & orange coat color must be sex-linked, since the color in the males seems to be determined by their mother, which in the case of cats has two X chromosomes and passes one of them down to the boys, since their fathers have to supply the Y. Do we all feel like we are back in undergraduate genetics?

Anyways, since there were no records of shared blood supply in developing kittens, the author hypothesizes that there must be some crossing over between the X and Y chromosomes that also accounts for the spermatogenesis of calico males being abnormal, wherein some sperm carry 17 and some 18 chromosomes (hint hint). Does this count as close to the correct response? I mean, chromosome nondisjunction is also a freaky thing to happen (yes I am being melodramatic, don’t come for me because freaky things are fun and nature is nothing if not a bit freaky) so maybe recombination occurring between two entirely different chromosomes (one of which is sad and small, Y chromosome I am referring to you) seems reasonable for scientists 100 years ago. Wow, we’ve come far!

TORTOISESHELL TOMCATS AND FREEMARTINS: A Note on the Occurrence of Fused Placentae in Cats

Free-mar-tins! Free-mar-tins!

Here we visit (again) the fact that some scientists spent years looking at cat placentas for fusions between kittens to explain the phenomenon of sterile tortoiseshell toms. One of them (Doncaster) died before the negative results of his hypothesis were reported. Bamber and Herdman went on to hypothesize that the phenomenon must be explained by a chromosomal abnormality, which Little (I can’t find a link to the exact paper, sadly) called a chromosomal nondisjunction (bingo!) several years prior. The article then goes on to describe (quite graphically to be honest, Bissonnette should have written horror novels as a hobby with these descriptive skills…) a dissection of a pregnant cat whereby an almost complete fusion of the placenta between two fetuses was found. While the fetal kittens were not developed enough to determine what sex they were, this finding does reveal the possibility of freemartins occurring in cats. Interestingly, Bissonnette is one of the early scientists who investigated the developmental causes of freemartin cattle, and completed much of the early work on intersex in animals. It then appears that he switched to studying the role of photoperiods in animal reproduction, and was even featured in a Time article in 1946, where I found this GEM of a quote:

Dr. Bissonnette washes his hands of man. Human beings, in breeding condition the year round, are not a photoperiodic species, says he.