About the author

Julia Harenčár is an evolutionary biologist passionate about combining ecology with genomics to understand plants. She is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Santa Cruz in Dr. Kathleen Kay’s Plant Evolution lab.

The story behind our recent article is riddled with modern science clichés; cancelled field seasons due to COVID, hunting down past collaborators and asking them to dig out half-decade old lab notebooks, and an initially resistant graduate student (that’s me) finding that their advisor was right all along.

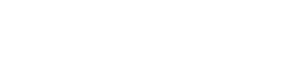

It all began when my 2020 field season was cancelled along with everything else. Instead, I used the time to generate a new reference genome to facilitate my work studying speciation and hybridization between two neotropical plants (spiral gingers – Costus species). I found a sister species to my focal pair in our greenhouse collection, C. lasius, and got to work generating a new genome. A year later, the pandemic raged on, and my hopes of returning to the field were dashed. My committee suggested I publish the genome I had created, and my advisor encouraged me to include the other reference genome for the genus (C. pulverulentus). I did not like this idea. The C. pulverulentus genome had been created several years earlier and involved people who had since moved on to jobs far and wide. I was not excited to track folks down and ask them to dig out old methodological details. But, I was already comparing the genomes out of curiosity, and my advisor pointed out that including the comparison in the publication would make it much more interesting than simply presenting the new genome. I reluctantly agreed because, despite my resistance to the boring leg work involved, I knew these plants both deserved publication, and that comparison would be valuable.

The Neotropical spiral gingers boast a long history of primarily ecological research that has helped shape our understanding of rapid tropical plant diversification. For example, the genome that was sequenced first of the two compared in our article belongs to C. pulverulentus. This plant is a key player in one of the first empirical studies finding evidence of reinforcement (selection directly increasing reproductive isolation; Kay and Schemske, 2008). The genome I assembled recently is a C. lasius genome. This species is a close relative of several species pairs the Kay lab is investigating, making it a key resource for the expanding genomic work in the Costus system.

Conveniently, C. Pulverulentus and C. lasius span the oldest node in the neotropical Costus phylogeny; their most recent common ancestor is the original Costus that arrived in Latin America about 3.5 million years ago and gave rise to the 60+ species now recognized (Maas et al., 2023). Despite 3.5 million years of divergence, we were intrigued to find that the genomes are very similar, with minimal chromosomal rearrangement. Contrast this with stick insects (Timema), as an example—I recently learned that these little critters’ genomes are riddled with chromosomal rearrangements, even between ecotypes of the same species (Patrik Nosil, personal communication)!

As genomes are sequenced and published at an ever-increasing rate thanks to decreases in sequencing costs and projects like the California Conservation Genomics Project (CCGP), we can begin to document this variation in the frequency and time scale of chromosomal rearrangements. This will be critical information as we grapple with the potential evolutionary role of chromosomal rearrangements.

So, I’ll admit it: my advisor was right again. I am glad I listened and am proud of the ultimate product. We will never know what may have come from the skipped field seasons. But, at least we used the forced indoor time to augment genomic resources for studying tropical plant evolution and to grow our knowledge of the time scales of chromosomal rearrangements.

References

Kay KM, Schemske DW (2008). Natural selection reinforces speciation in a radiation of neotropical rainforest plants. Evolution 62: 2628–2642.

Maas PJM, Maas-van de Kamer H, André T, Skinner D, Valderrama E, Specht CD (2023). Eighteen new species of Neotropical Costaceae (Zingiberales). PK 222: 75–127.